Parodies of the Ideal: Miles Aldridge’s New Utopias

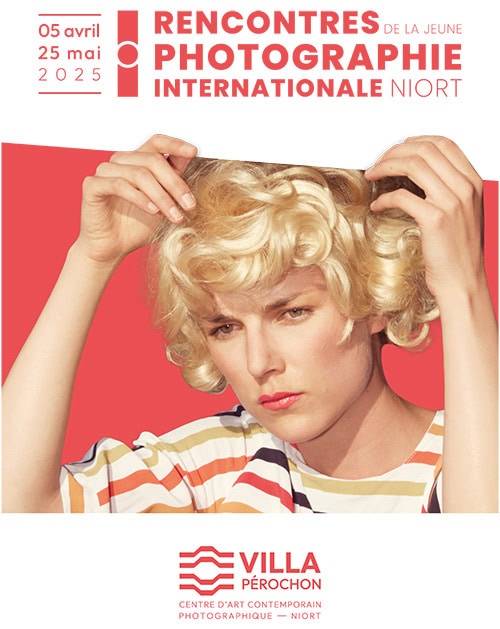

Inspired by the aesthetics of consumer culture whilst simultaneously drawing on art historical tropes, Miles Aldridge’s series ‘New Utopias’ (2018) explores the tragic pursuit of an idealised existence. Playing with the term ‘domestic goddess’, Aldridge presents us with a string of manicured women sporting bouffant hairstyles, performing various ‘housewife’ tasks, such as making breakfast or joyfully carving a ham. When compared to iconic representations of idealised women from art history —such as Botticelli’s celestial representation of Venus, the Roman goddess of love—we notice a stark decline. The weight of domestic perfection hangs heavy, and the women in ‘New Utopias’ look tense, disappointed, frustrated, distracted. Aldridge satirises societal norms and strained ideals, inviting us to find comic relief in the absurd.

Through their falsity, the photographs could be mistaken for paintings when viewed from afar. Shooting all his work on colour negative, Aldridge describes how “with film you get this beautiful kind of lustre that feels more like a painting. I process it quite aggressively to bring up the colours.” Alongside his saturated shades of block colour, which exclude tone and depth, an all-too-perfect sheen lends the pictures a manufactured and unrealistic look. The aesthetic recalls advertisements from the pages of glossy magazines in 1950s America.

In previous series, Aldridge has drawn from early Renaissance art history and its depiction of the feminine to inspire his own portraits of modern day celebrities. Yet, in ‘New Utopias’, Aldridge plays with the idea of tragedy as presented in Renaissance tableaux by incorporating an element of drama into his narratives. His cinematic scenarios brim with tension, but provide little context. In this way, Aldridge’s distressed looking subjects become more akin to ‘tragic heroes’ than Roman goddesses.

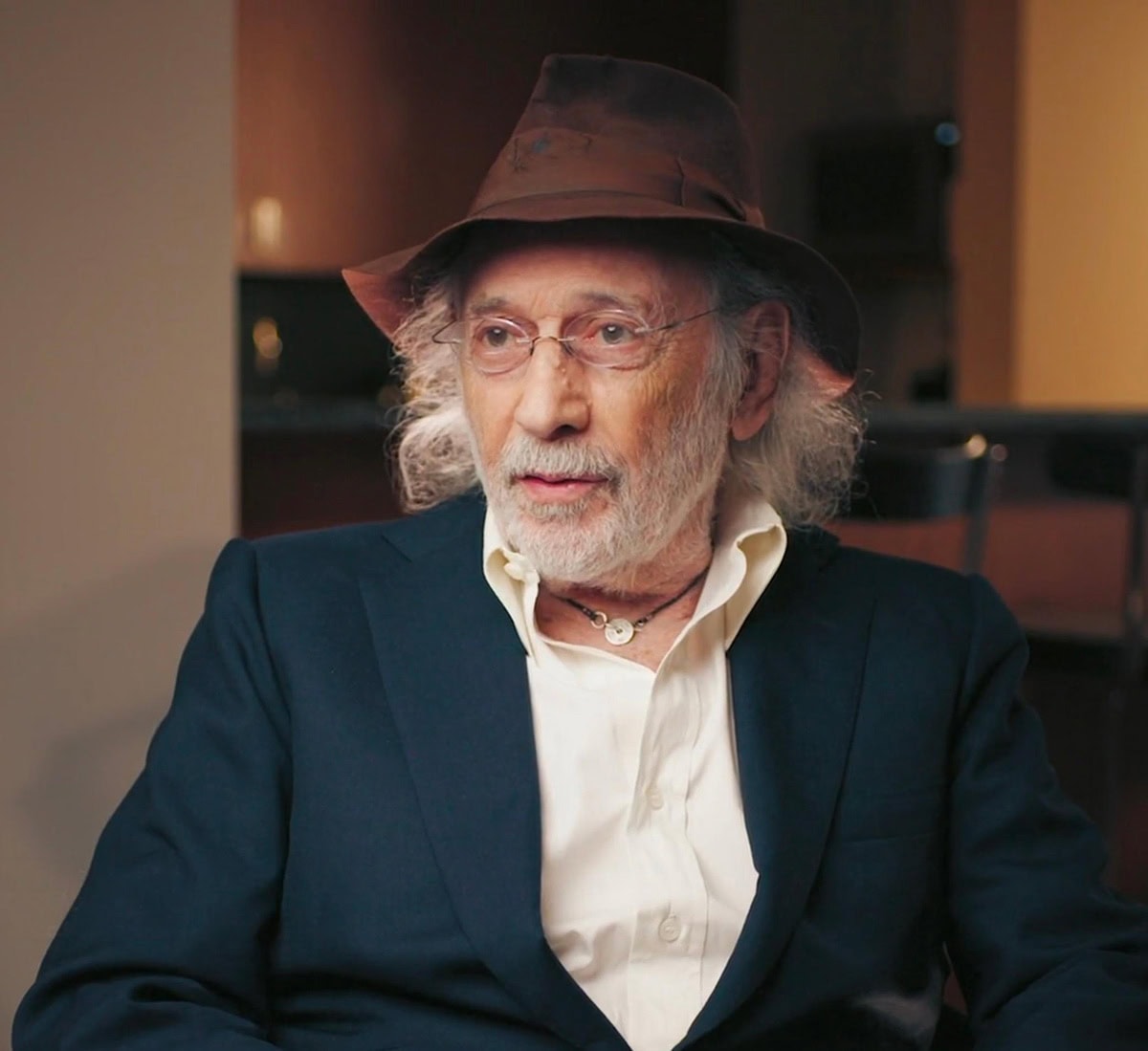

In a recent interview published by the V&A, Aldridge discusses how influential Franca Sozzani, the editor-in-chief of Vogue Italia, was for his creative development. He explains that “Franca gave me the freedom to express myself through my work and over time I started to return to images of my childhood. I would revisit memories of my mother as a trapped housewife from a broken marriage. She wore this inscrutable face that you couldn’t read. If you overheard her phone calls or read her letters, you knew she was falling apart inside, but on the surface she didn’t show any of that.”

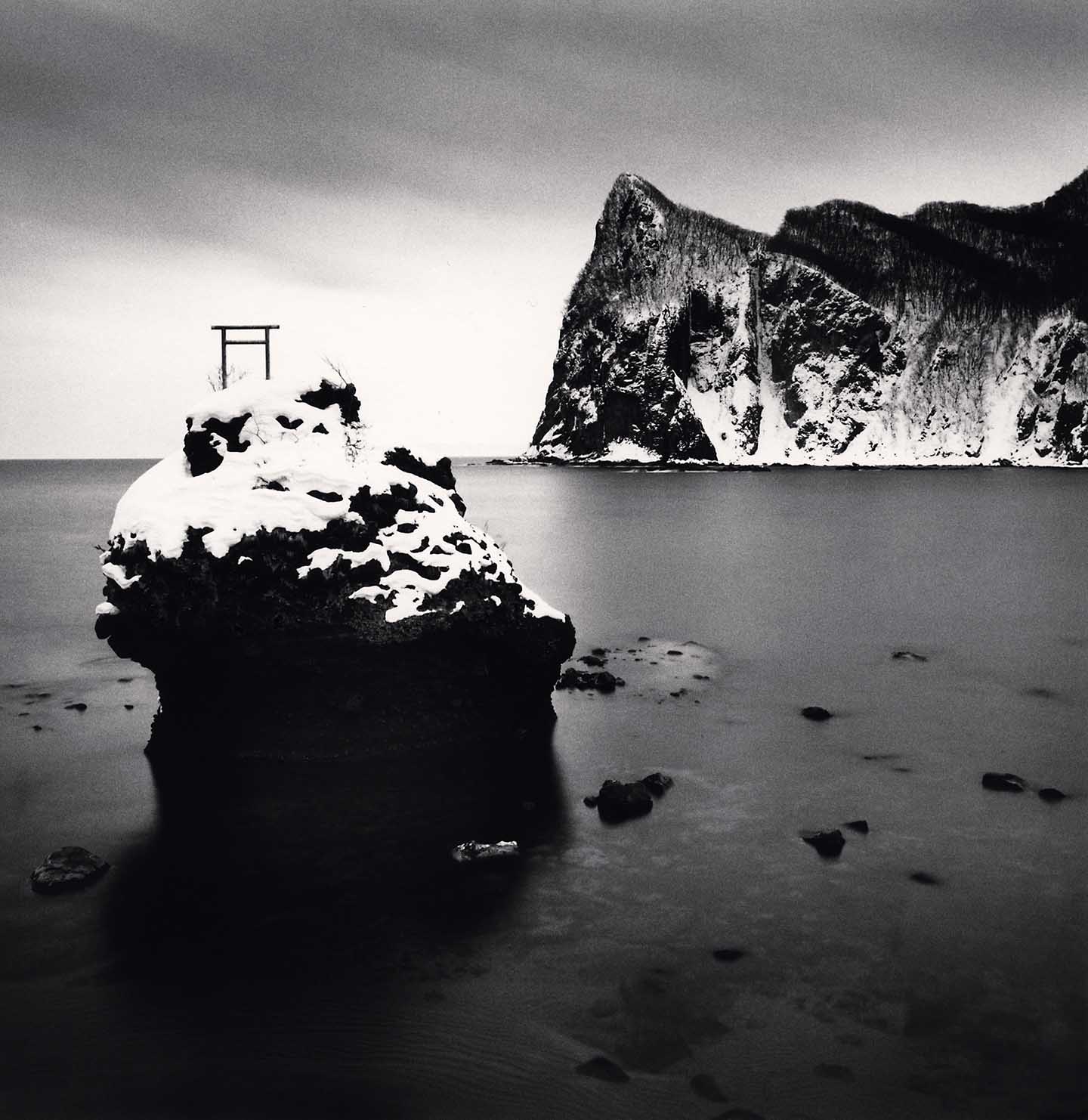

After his eccentric father moved out of their boldly-decorated family home, Aldridge describes how his mother “was living in the ruins of this psychedelic palace where my sister and I grew up. The homes depicted in my pictures rarely have windows. They’re like chromatic prisons with no views of the outside world… It was only later in my life, when I was asked in an interview about the influence of my father and mother on my work, that I realised that my mother, this close-lipped woman, cleaning and cooking all the time, was the woman in my photographs.”

This exploration of his childhood reaches beyond the ‘New Utopias’ series. In Aldridge’s cinematic narratives, we often see glamorous women at breaking point, surrounded by various smashed homeware. “Some of the dramas and some of the violence I saw at home at a young age, all the screaming and shouting, I revisited with fictional characters… There was never a specific incident like the one depicted in ‘I Only Want You To Love Me #1’ (2011), with all of the food thrown across the floor, but I can certainly remember dinners being thrown across the wall. To add another layer to that shot, the model is my half-sister, Ruby. She is the youngest of all eight of us and she had just started modelling then. My half-sister acting as my mother is like something from a Greek tragedy.”

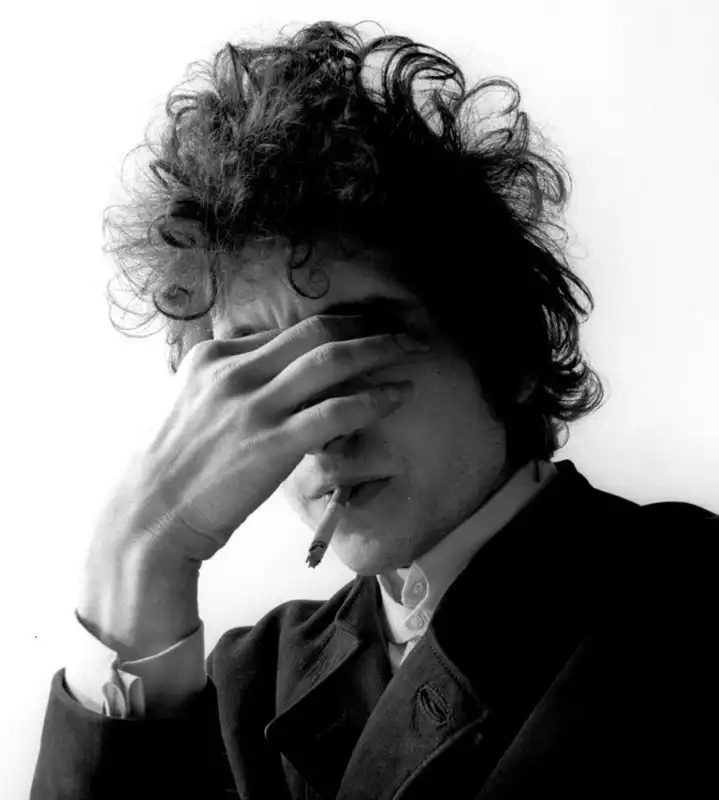

There are said to be three key elements which define a Greek tragedy: hamartia (a hero’s tragic flaw which ultimately leads to their downfall), anagnorisis (when the tragic hero recognises something about themselves, some depth to their identity that spurs a change in action), and peripeteia (the ‘reversal of fortune’ in the plot which marks the protagonist’s descent towards tragedy). With this in mind, Aldridge seems to channel the anagnorisis stage of a narrative in his work. He says, “The fictional characters I create are always in this moment of questioning themselves. The characters are searching for something, but their means to find it are very strange, like adorning themselves with expensive clothes… I want it to feel like the subject is thinking deeply because their life is so confusing.”

Aldridge explains how his mother sadly passed away, just as he was beginning his career in photography. “What made me want to tell these stories was the ‘unfinishedness’ of her life and seeing that domestic misery – being let down by the promise of marriage… [It] left a gigantic question mark for me; ‘Who was this woman?’”

With a distinctive style that blurs the lines between fashion, fine art and surrealism, Aldridge breathed new life into the often predictable advertisement world. In a realm where conformity and clichés can reign supreme, Aldridge’s work dares to be different, infusing a dose of unpredictability and comic relief into every campaign. But beneath the glossy surface lies an existential exploration of human emotion. Especially prominent in ‘New Utopias’, Aldridge parodies society’s obsession with image and beauty, highlighting the loneliness and emptiness that can result from the pursuit of an idealised existence.