‘Reading the Landscape’: A Three-Part Series by Olaf Otto Becker

Reading the Landscape shows three states of nature in the primary forests of Indonesia and Malaysia: intact nature, ravaged nature, and artificial nature. Altogether, the project documents a fatal ecological and economic process that has progressed beyond the point of reversibility.

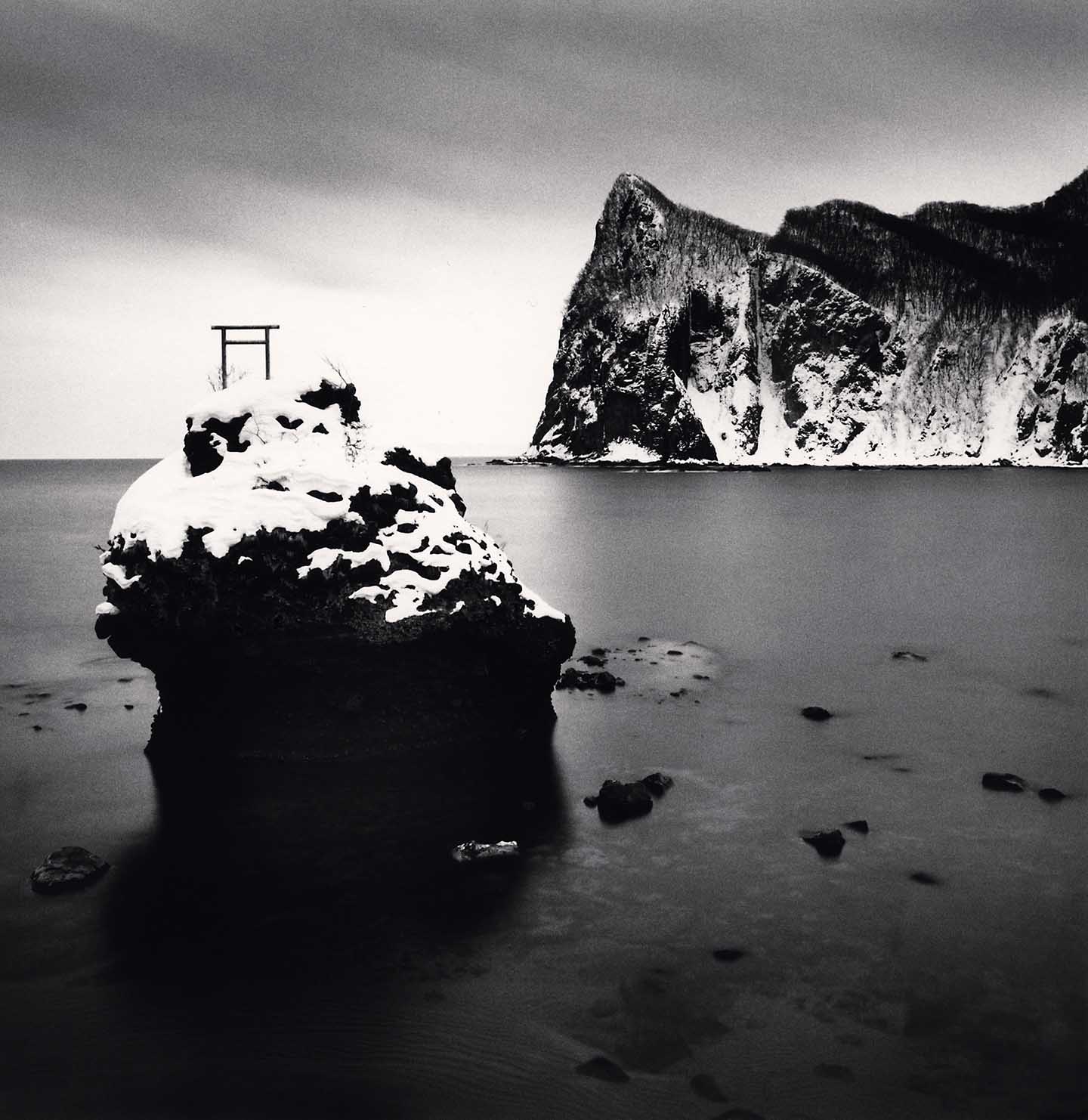

Olaf Otto Becker has spent his career photographing the wildest places on the planets – documenting fragile ecosystems in every hemisphere. His 2014 series, Reading the Landscape, is divided into three chapters, documenting how modernity has shaped our most ancient of forests. Shot spectacularly in large format, the photographs in the first of the chapters capture the winding rivers, towering trees and wild foliage found in the dense, Southeast Asian rainforest. The images are strikingly beautiful, yet they also serve as the prologue of the series, a deliberately powerful reminder of the importance of preserving these environments. As we work our way through the chronology of the book, the fragility of these forests is slowly and dramatically revealed.

Becker grips the viewer with these vast and verdant landscape studies. In a few early images, a light mist drapes over the treetops, creating an emerging sense of unease as the thick vegetation in the background is swallowed by a sea of mystifying white. Yet in other images from this first chapter, it feels like everything is alive, as if the forest is breathing. The forest appears bright and vibrant as it shimmers in the sunlight. When viewed in large-format, the clarity and detail of his photographs engulf the viewer within the rainforest.

Deforestation is the issue that lies at the heart of the series, and this is revealed as we move from chapter one into chapter two. Becker contrasts the primeval ecosystems of the first chapter with large swaths of abraded territory. The magnificent tableau’s of Becker’s green and pleasant prelude are ripped away as the pages turn: luscious greens are replaced with earthy browns in exposed terrains that have been stripped bare. The second chapter of his series serves to reveal what happens when internationally operating companies clear large tracts of the rainforest.

These forests, which are some of the oldest and most biologically diverse in the world, are being cleared at an alarming rate to make way for agricultural and industrial development. It’s a well-known fact that the production of palm oil is one of the primary drivers of deforestation in Southeast Asia. A global demand for palm oil boomed in the late 20th century, when it was used in a wide range of products including food, cosmetics, and biofuels. The expansion of palm oil plantations has led to the clearing of vast tracts of forest, the displacement of local communities, and the destruction of critical habitat for endangered species including the orangutan and Sumatran tiger. Other factors contributing to deforestation include illegal logging, mining, and slash-and-burn agriculture, which involves clearing land by burning the forest and planting crops. These practices release large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, having an enormous impact on climate change.

Efforts are being made to address the issue, including the development of sustainable forestry practices and the establishment of protected areas. However, Becker believes much more needs to be done to ensure the conservation of these critical ecosystems, and to mitigate the impacts of their destruction. The project reveals the paradoxical nature of the current moment, that society is responsible for both the destruction of primary habitats and the attempts to protect them.

In the third and final chapter, Becker presents a number of artificial ‘forests’ conceived by international architects to insert greenery into urban spaces. Photographing in various locations around Singapore – a mere 500 km from the rainforests in central Malaysia – Becker documents hotels, sky-gardens and nature parks laden in artificial foliage, remarking that “the inventions of the best architects in the world cannot replace destroyed habitats and the complex ecosystem.” Here, the photographer highlights the irony in the attempts made by entities in financial capitals like Singapore to ransack the rainforest, whilst seeking its natural beauty for the well-being and aesthetic satisfaction of a city’s inhabitants.

By accumulating these three chapters into a unified series, Becker presents a fraught, political message about the immediate and devastating consequences of climate change. Juxtaposed with a seductive first chapter comprised of majestic, leafy landscapes, Becker’s second and third chapters invite the viewer to consider their own complicity in the destruction of natural landscapes such as these.