The Definitive Guide To Photographic Prints

21st April 2023

In the world of modern photography, prints are generally divided into two categories. The first is darkroom printing, which lies at the core of the medium, and the second is digital printing.

The traditional chemical process usually involves using a film negative and an optical enlarger to project the image onto a paper that’s treated with light-sensitive chemicals. Through the enlarger, the photographer can manipulate the aperture, focus and exposure time to achieve their desired result. After exposure, the paper is submerged in a series of chemical baths to develop, stop, and fix the image. Digital printing, however, involves an image file and a printer that uses inkjet or dye-sublimation technology to deposit ink onto paper.

While darkroom prints often have a unique aesthetic characterised by grain, tonal richness, and a handmade quality; digital prints can have a more polished and precise appearance. Both methods have their place in modern photography, and the choice between them depends on the photographer’s preferences, artistic vision, and intended outcome. When acquiring photography, there’s a plethora of medium-specific terminology that’s worth getting your head around, as the printing process impacts the final result and can contribute to the value of the print. Here are some of the methods you’re likely to encounter, spanning both digital and darkroom processes:

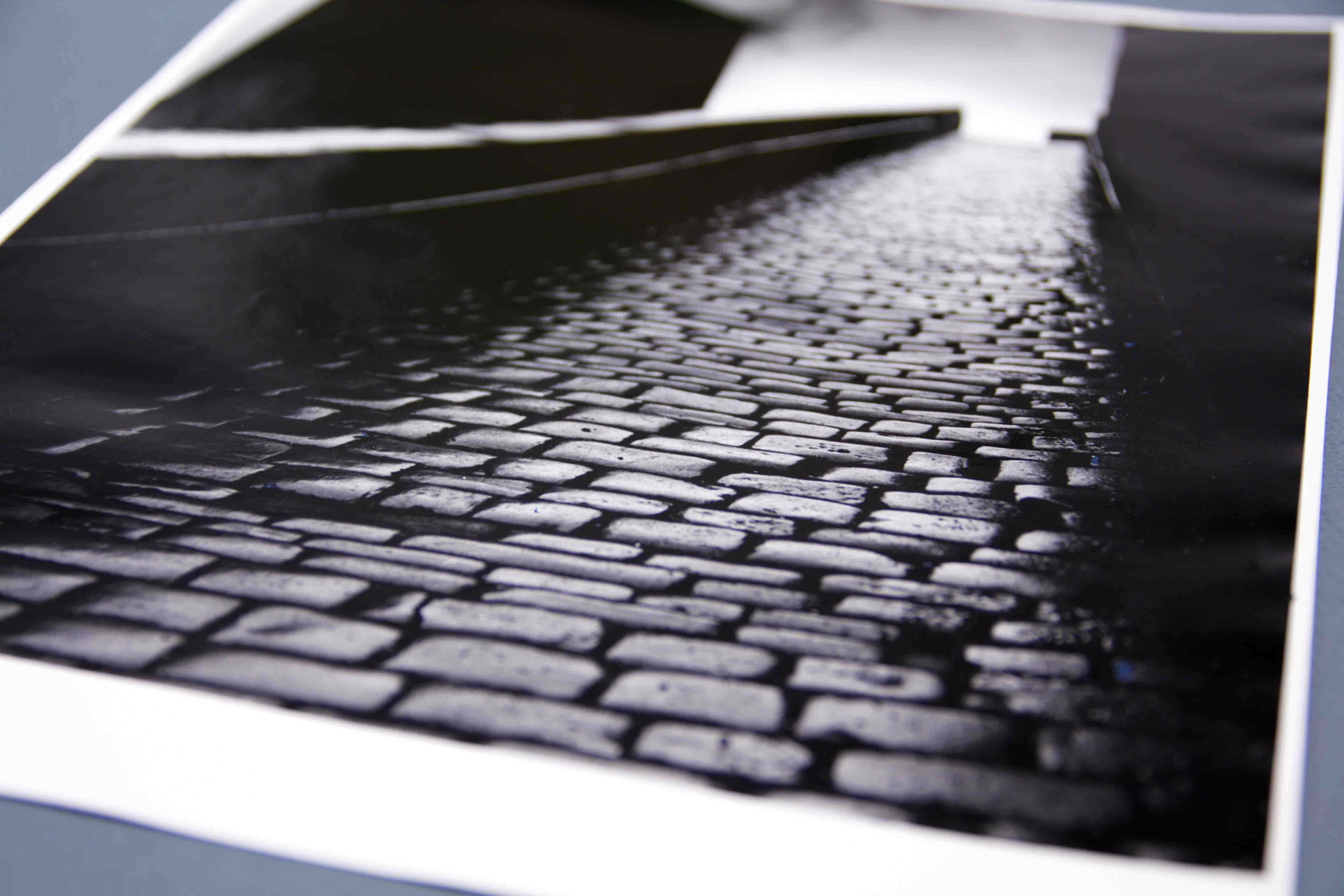

Silver Gelatin Prints

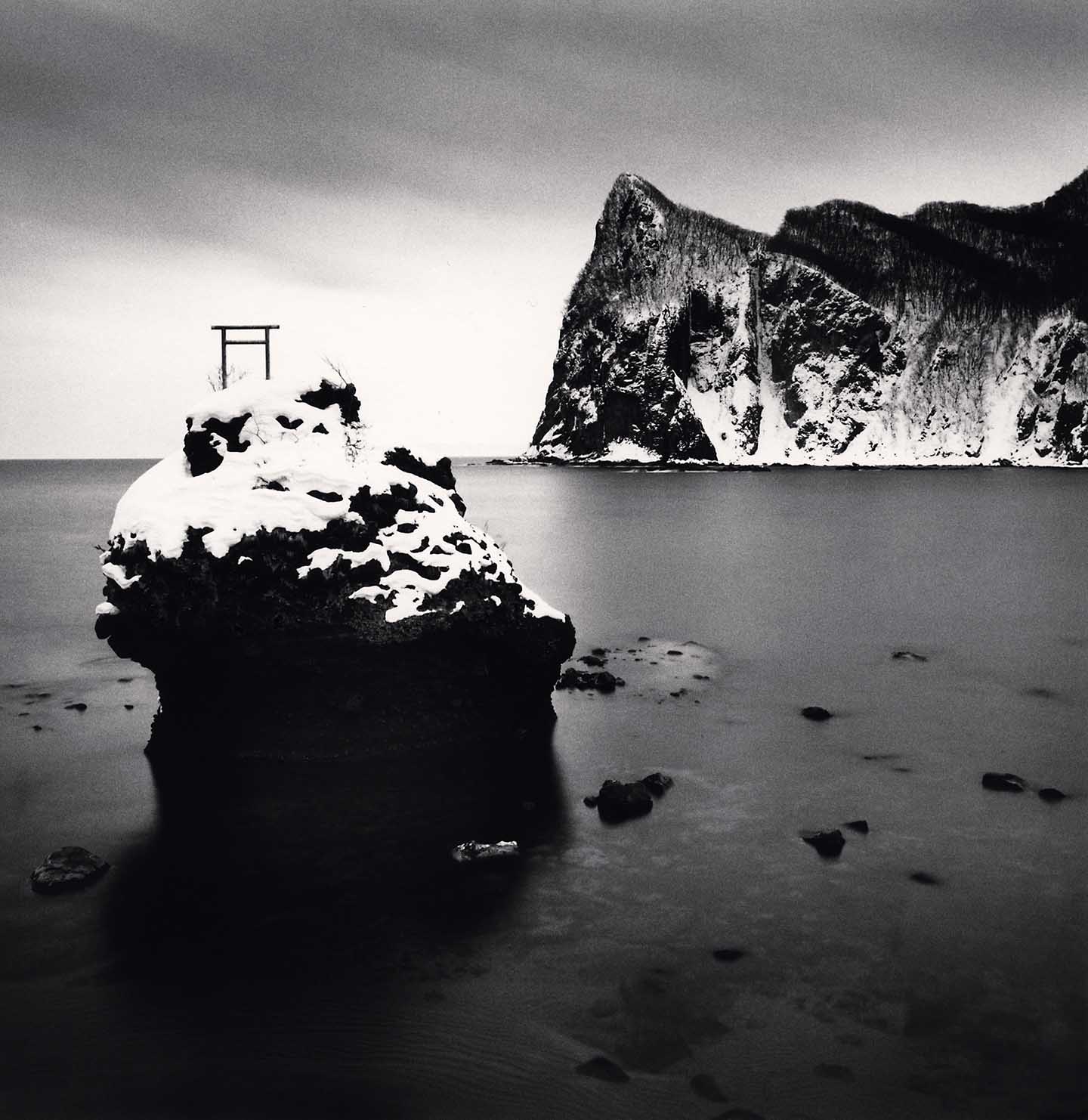

The silver gelatin printing process was founded in 1871 and is the most common darkroom practice for black-and-white prints. The method is widely associated with photographers from the early-20th century, but remains popular today for its traditional aesthetic which is characterised by strong blacks and dark whites. While the general process is outlined above, the defining feature of the silver gelatin process is that the paper is coated with a gelatin emulsion that contains silver halide crystals. These crystals are sensitive to light and react when exposed to it, giving the print a distinct, luminous quality. Silver gelatin prints can be made on a wide variety of paper types, which can have great effect on the texture of the image. So when buying photography, you may find that the paper is specified along with the process.

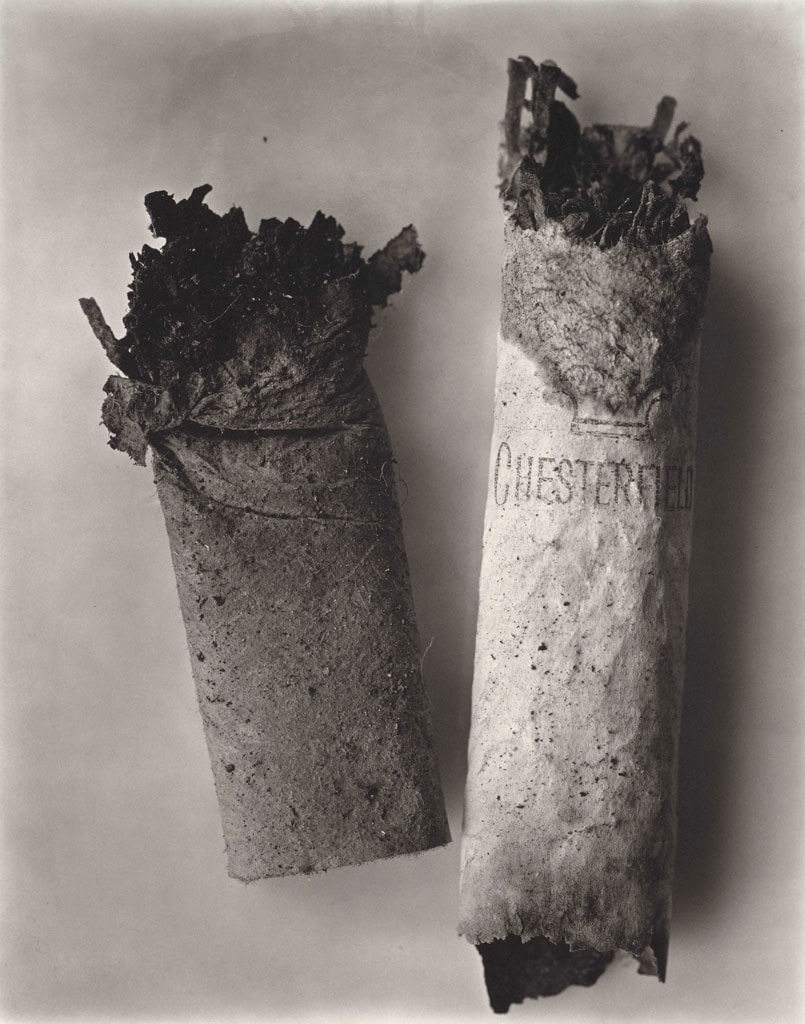

Platinum Palladium Prints

Platinum Palladium is another black-and-white darkroom process that originated in the 19th century but has continued to be used by contemporary photographers. Much like the silver gelatin process, Platinum printing involves hand-coating a paper substrate with a light-sensitive solution—this time containing platinum and/or palladium salts rather than silver crystals. Platinum is a precious metal known for its strength and durability, and the salts need to be exposed to ultraviolet light to create a latent image. While highly regarded for unique aesthetic and archival qualities, platinum printing is also considered to be an expensive, labour-intensive and technically challenging process. Yet it continues to be appreciated and practised by photographers who value the rich tonal gradations, luminous highlights, and deep shadows that platinum printing allows.

Pigment Prints

Pigment prints are made by digital inkjet printers. These printers mix pigment-based inks to create specific hues and use fine nozzles to spray the ink onto paper in precise detail. The term giclée refers specifically to fine art inkjet prints—it was coined in the 1990’s by a French printmaker who aimed to reverse the negative connotations associated with inkjet printers. Today, inkjet or giclée prints are generally referred to by the kind of ink used. Most consumer-level printers use dye-based inks, which are composed of a colourant that’s fully dissolved in liquid. More valued by photographers, though, are pigment-based inks, which gain their hue from powdered substances suspended in liquid. However, because pigment is sensitive to light, the colour of these prints can shift or even fade over time, which is why many museums store their works in carefully regulated environments. Archival pigment prints were then developed to contain a more stable dye, making them more suitable for long term storage. While archival prints are said to withstand light for over 100 years, storing inkjet prints away from light will protect their longevity.

Chromogenic Prints

Chromogenic prints, also known as ‘C-types’, can be produced both digitally and in the darkroom. It is a reliable process that has been the dominant method of colour printing since it was first developed in 1935. Originally, it was made up of three gelatin layers containing cyan, magenta and yellow dyes, which together creates a full-colour image. The chromogenic process gained popularity in 1942 through Kodak’s ‘Kodacolor’ prints which were hailed for their ease, consistency, quality and affordability.

This convenience was heightened by the invention of Digital C-type’s. For this process, C-type printers use LEDs or lasers to project an image onto treated paper (as opposed to projecting film through an enlarger), which is then developed along the same chemical process as above, but with automated machinery. However, C-type’s can also be produced as a hybrid of digital and darkroom processes, where digital images are projected using laser technology onto paper, which is followed by the traditional wet process.

C-types can be prone to colour shift or fading without archival framing and minimal exposure to direct sunlight. However, a particularly desirable quality to C-type printing is the ability to produce large scale prints. Even today, C-type printers can produce images as wide as 3 metres, which is considerably larger than the maximum scale produced by inkjet printers.

Dye Transfer Prints

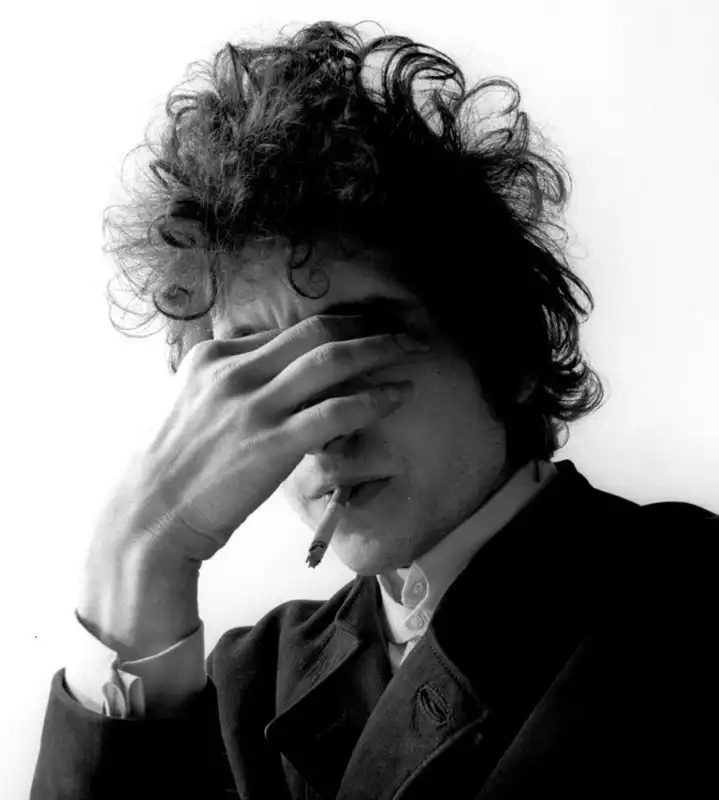

Dye transfer printing is an intricate full-colour photographic process that emerged in the mid-20th century and gained popularity for its unparalleled accuracy and vibrancy. The process involves three layers of dye (cyan, magenta, and yellow) that are applied by hand to one emulsion layer. It is a meticulous registration process where the dyes are transferred onto the print one at a time to produce a wide spectrum of colours. Like the Chromogenic process, Kodak popularised dye transfers in the 1940s but discontinued the process in the mid 1990s. Naturally, this has greatly increased the value of many works sold today by photographers working with dye transfer. This is especially true for artists like Joel Meyerowitz, William Eggleston and Ernst Haas, who were the pioneers of colour photography and early adopters of dye transfer prints.

Cibachrome / Ilfochrome Prints

Cibachrome—often known as Ilfochrome or ‘dye destruction’—is a unique and specialised chrome process that produces high-quality, vibrant, and durable prints. For this process, a positive transparency is exposed onto a photosensitive paper coated with multiple emulsion layers containing colour-forming dyes. During the development and processing steps, these dyes are selectively destroyed by a bleaching agent, leaving behind pure colour dyes that are highly stable and resistant to fading. Due to its technical complexity and costly materials, Cibachrome/Ilfochrome printing has been predominantly used by professional photographers and fine art printers. However, its unique aesthetic and archival qualities have made it a sought-after process for collectors and enthusiasts who appreciate the beauty and longevity of this exceptional printing technique.