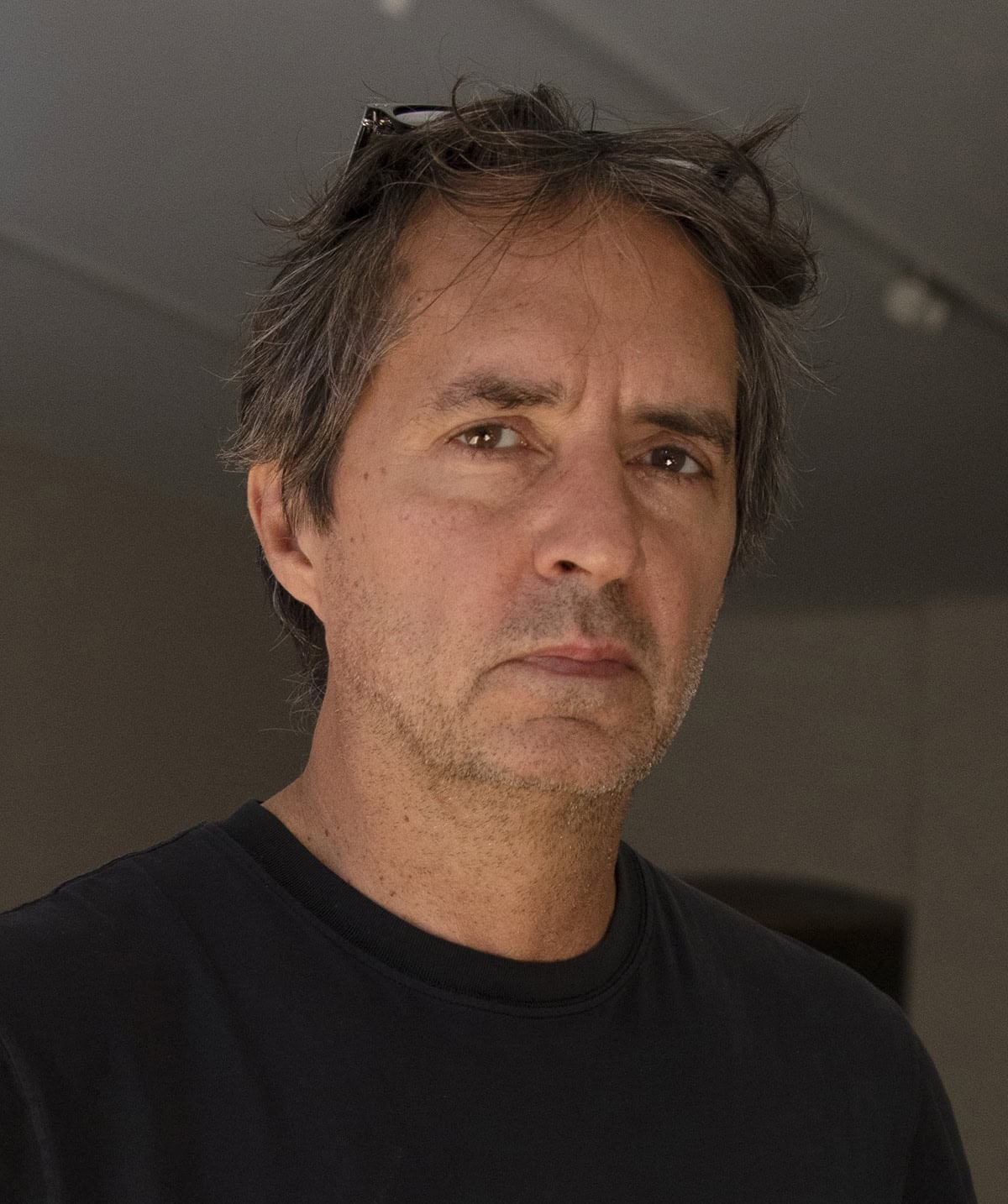

An Interview with Andrew Moore

After our online exhibition earlier this year, announcing our new representation of Andrew Moore, we sat down with the photographer to discuss his work and practice. In this interview, Moore discusses his early interest in history, his father’s influence as an architect, and shares a harrowing family story that had a lasting influence on him and his work. We also discuss his preference for shooting in large-format and how colour is the primary motivation of all his imagery. With a body of work that explores various interiors and exteriors, Moore describes some of his favourite images from his career, explaining that he sees interiors as portraits, or as portraits of a state of mind.

Francesca:

Your projects often explore the intersection of history, architecture, and social change. Can you discuss these influences on your work?

Andrew:

I’ve always loved history. The first time I ever travelled abroad was to England when I was a child. I grew up in New England, so things there were relatively old, but I remember feeling struck by how old things were in England. I liked seeing evidence of the past—small remnants from centuries before—still lingering on in the present. As a child, this trip really piqued my imagination. Those little historic clues illuminated a whole world for me.

My interest in architecture is a similar story, really. My Dad was an architect. So as a kid we would often visit building sites or projects that were in progress. One time, I remember walking around a high school that was under construction. There wasn’t much there, only really a few walls, but my Dad would say, “this will be the gymnasium”, and “the classrooms will be here”. I got used to imagining architecture, not just as buildings, but as spaces that people inhabited. I think those experiences informed my work a lot. But I actually believe I have a kind of sixth sense about architecture. It’s hard to explain, but I can look at a building and I just get a feeling about it. I think, “There’s something intriguing about this place and I have to get inside.”

As for social change, this is really the narrative of the work. It’s the more personal, human level. What people are wearing, what the cars look like, the signs. Walker Evans once said, “to see a good picture, you need to wait 40 years”, because things become more interesting as they age. So, I’ve really tried to combine all those elements; history, architecture and the story.

Francesca:

Decay and resilience are also big themes. Can you describe what draws you to these aesthetics and why?

Andrew:

So on my father’s side, there’s a long string of ancestors that go back to the 1600s in America. One strain of this family ended up making a lot of money, buying and selling land in Cleveland. There was this one woman named Georgia Stone, who had millions of dollars in the bank, but people had forgotten about her. She lived like a hermit in this large house, and in her old age she had become a bit mad. When she died, my Dad was her closest relative, so he became executor of the estate. My parents went to clean out the house and came across a rolled-up carpet, which had a skeleton of a dog inside. She actually ended up dying of starvation, alone in this mansion. It’s almost like a Miss Havisham scenario. This story really affected me as a child. I was struck by the idea that even with wealth and privilege, everything can go very wrong.

Andrew:

In later years, I learnt that resilience is often found at the other side of decay, which is a theme that really shone through for me in the Cuban series. Havana is a beautiful city, but it’s barely functional. The buildings are falling apart. Yet the Cuban people just work with what they have. There’s bright colour everywhere, they repurpose anything and everything, nothing gets thrown away. I feel like resilience and decay are two sides of the same coin and I’m always looking for this dichotomy in my work—sadness and beauty, hope and despair. I think some of my best images are the photographs that include this emotional complexity.

Francesca:

What initially drew you to photography?

Andrew:

My mother edited art books and my father was an amateur photographer. He loved photography. I actually recently discovered a series of pictures that he made in Cuba, in 1940. We built a small dark room in our house, together with my brother, so I learnt how to develop film when I was a teenager.

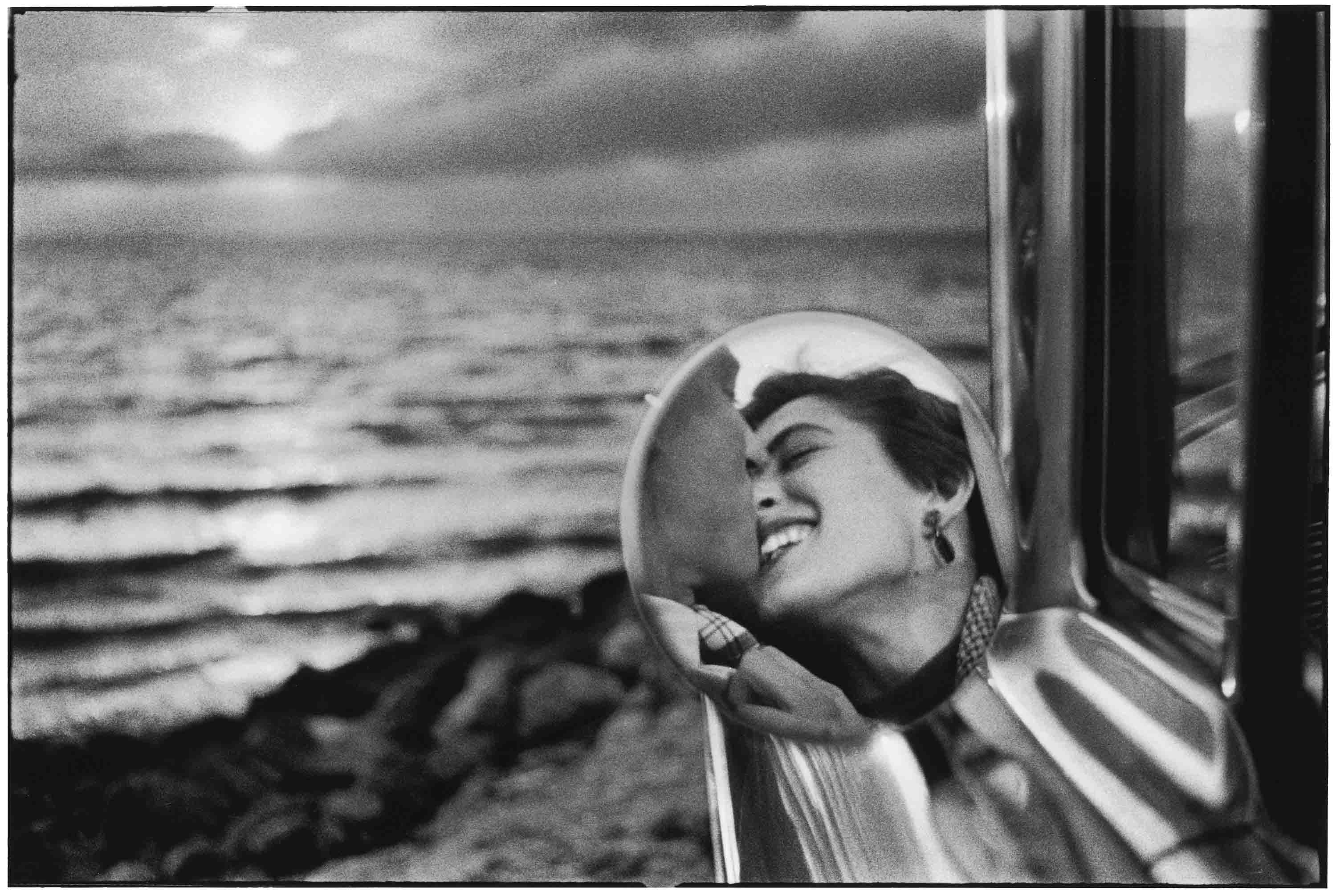

I took painting classes initially at college, but they happened to have an excellent photography teacher there, so I started taking his class instead. He turned out to be an amazing influence on my life. This was the mid-1970s, when colour photography became more widely available and my college installed a small colour darkroom. One year, Joel Meyerowitz came and gave a lecture, and he showed us some large dye transfers of his street work. He was also shooting 8×10 colour negatives up in Cape Cod, which were some of the first colour contact prints I’d seen. I thought, “this is something I could really get into”. So, I chose photography because it could tell the story, because it was flexible, and I didn’t really draw that well anyway. But mostly because this new world of colour was so exciting. I was just very fortunate to be in the right place at the right time.

Francesca:

Can you describe how you approach colour in your work. Are you often led by colour alone or is it more of a secondary factor?

Andrew:

It’s absolutely the primary motivation for my pictures. I know that sounds very decorative, but if I don’t have that emotional resonance with a colour, the picture won’t work. It’s essential for me. If I find a scene that has great colour, I continue to refine the tones in the printing process at my studio. Fleshing out the colours and all the colour relationships is a big part of my process.

Francesca:

Do you always shoot in large-format? What led you to photograph in this way?

Andrew:

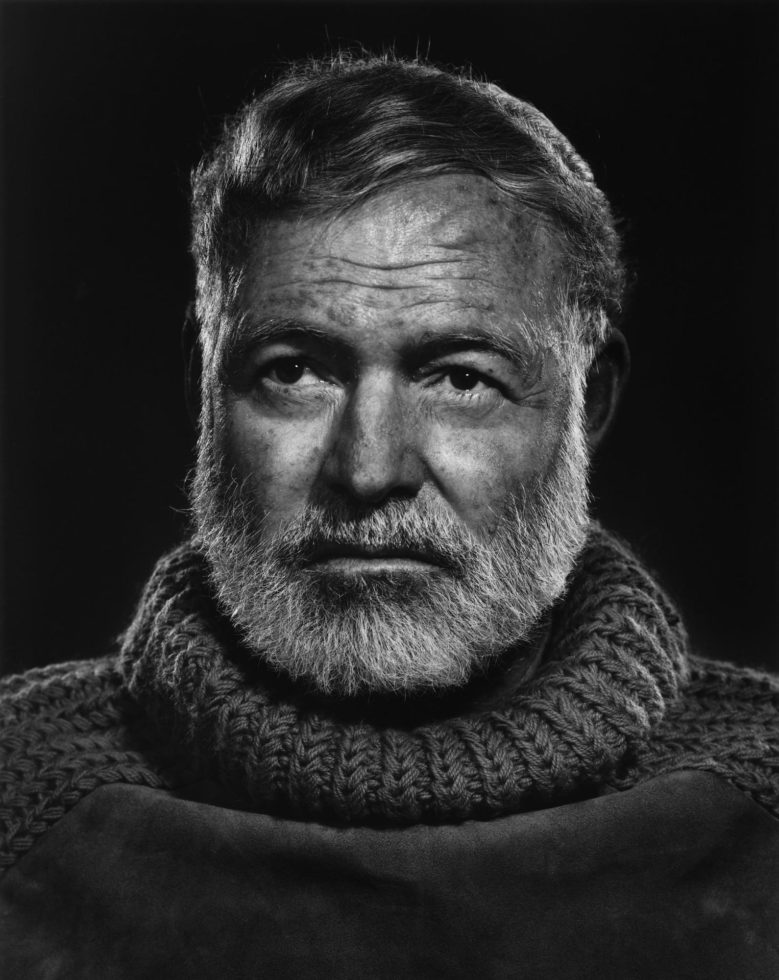

My teacher at Princeton was Emmet Gowin, and he was working primarily with an 8×10 camera. I just thought it was the most amazing thing ever. There are a thousand things that can go wrong, and you have to make all the mistakes. But I loved looking through the glass, and the sharpness of it—it was sharper than you could see. It’s very contemplative, but also challenging, and it’s the perfect tool for photographic architecture. So from 19 years-old, I was shooting 8×10 pretty much up until 2017. I used a Phase One for the ‘Dirt Meridian’ project because the digital files were good enough to make very beautiful prints for a gallery. Now, I work with a Phase One and an Alpa. For me, it’s like having an 8×10. So I’m still kind of a large-format photographer, but I’m doing it digitally.

Francesca:

Which of your series did you most enjoy making?

Andrew:

I liked all the series. ‘Dirt Meridian’ was the most challenging, because the project took ten years. The series in Detroit was the most thrilling and viscerally exciting. The Cuban project was the most magical. But my favourite series is probably between Cuba and ‘Detroit Disassembled’.

Francesca:

Interiors and exteriors are a consistent theme throughout your work. While there are often no people in your photographs, it can be an intimate experience to photograph in someone’s home. The exterior of a building, however, is much less personal.

Andrew:

Absolutely. The interior is like a portrait of someone’s mind. You’re not just in a building, you’re in someones existence. You’re seeing their whole life, as if it’s been turned inside out into a space. It’s deeply narrative, on so many levels. The exterior is more like a facade, or a secret. It’s giving a few clues, but the mystery remains. Interiors are definitely my favourite because I love creating layers and pockets of depth. I’m interested in flat space and deep space, the dimensionality almost becomes a temporality.

Francesca:

Can you tell us an interesting story behind one of your photographs? Or if you have a favourite image from your archive, can you explain why?

Andrew:

One of my favourite stories is an image I made called ‘En Casa con los Alonso’ (1999), which is part of the Cuban series. It shows two people watching a blank TV screen in a living room. There’s a family called the Alonso’s, who lived in an enormous mansion in Vedado, which is a 20th century suburb of Havana. They were from a very wealthy family, I think his grandfather had been one of the founders of the railroads in Cuba. After Fidel came to power, many of the wealthy families left Cuba within a few years. But for reasons I’m not privy to, they decided to stay. They were permitted to keep their house, but they didn’t have any income. So over the years, they were forced to sell all their belongings to foreign diplomats for cash; their paintings, tapestries, furniture. I was photographing various parts of their beautiful house, and walked around the corner to find the grandmother and a friend watching Brazilian soap operas on the television. The picture shows this beautiful early 20th century interior with 15-foot ceilings, marble floors, French doors, a crystal chandelier—sitting alongside some beach chairs and old, mismatched furniture. The ceiling is peeling away because of the salt water from the ocean. But the floor was always sparkling clean, the family always dressed very formally.

This picture was published in my first book, along with a few others from the Alonso house [pictured above]. Then about 10 years later, I got a message saying “Please tell Andrew Moore thank you. Ever since he published his photograph, we’ve had many photographers asking to use our house for photo shoots and fashion events. Now we make a living by renting out our house.” It’s a wonderful twist to the story. The photograph looks kind of sad, but there’s a certain pathos to the image, in that they really had nothing left in the house to sell, but were able to make money back from the charm of their home.

Of course, the story ties back to my old family history. The imagery is deep in my soul. It’s the idea of people living in these beautiful, grand houses that are falling apart around them. As if the people are preserved there, in dignity. It ties back to telling a whole life story within the context of one room.

Francesca:

Looking ahead, will you continue to create photographic projects? Are there particular places, subjects, or themes you are eager to explore?

Andrew:

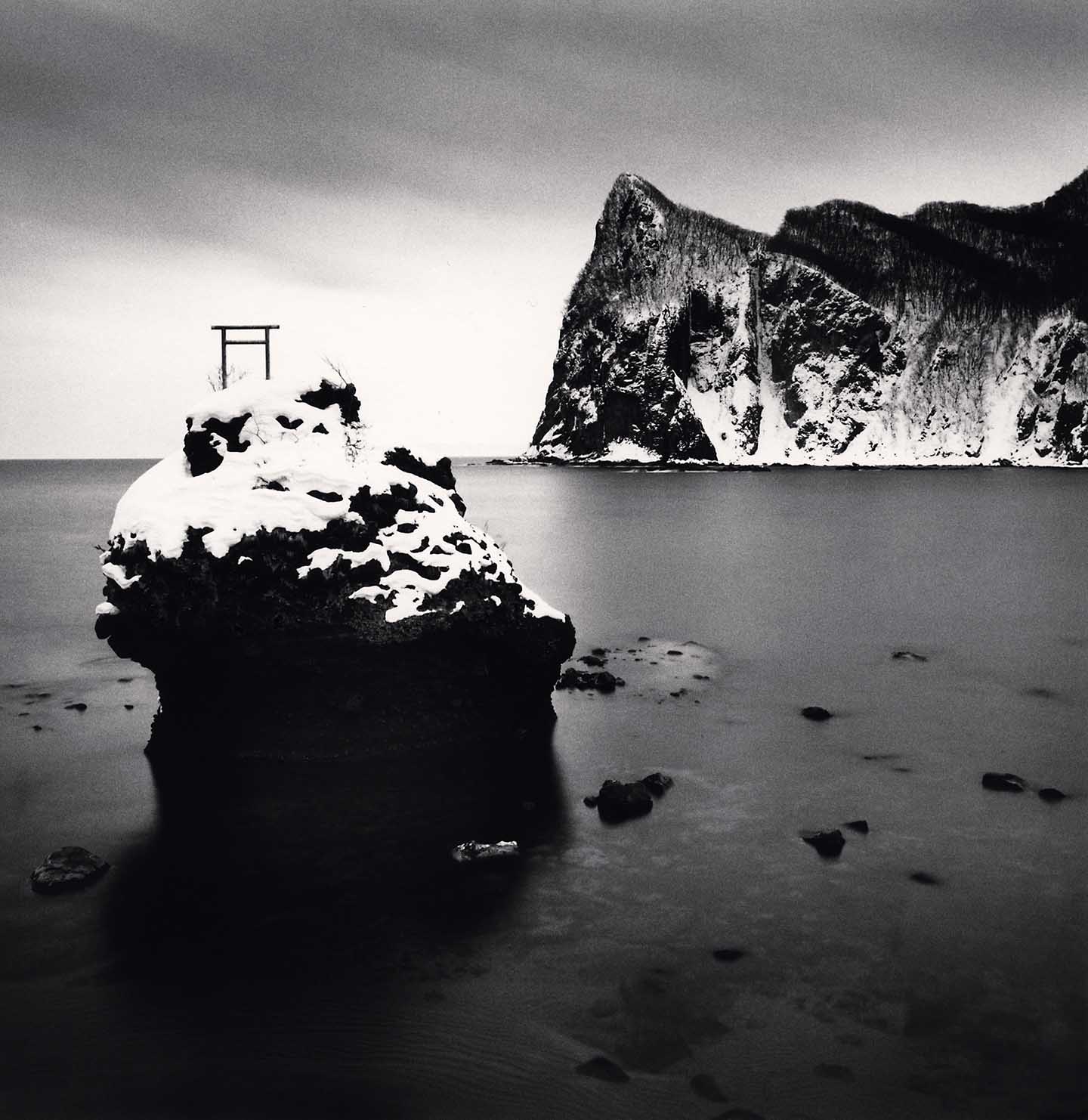

A friend of mine is a professor of Literature and recently introduced me to this term ‘ecogothic’, an aesthetic that refers to the sinister side of nature. It was first introduced in the 20-teens but it derived from American literature, writers such as Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne. It blends horror, gothic and the supernatural with themes like decay and other environmental issues. So I’ve been pivoting my work and using that term as a lodestar, looking at the darker side of nature, as opposed to it being sublime and God-like. Eventually though I want to go somewhere further afield, like Australia, Mexico City, or maybe Pakistan. I don’t know, stay tuned!

FeaturedAndrew Moore

The ArtistAndrew Moore is widely acclaimed for his long-term photographic series, which record the effect of time on natural and built landscapes.

Artist Page